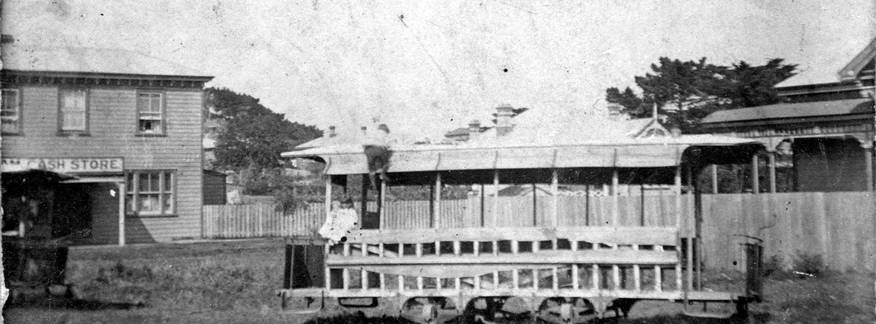

Victoria Wharf

Trams began their journey from the foot of Victoria Wharf. They were scheduled synchronously with the Devonport Steam Ferry Company’s timetable, although neither company was known for its punctuality. A planned combination ticket office and waiting room at the foot of the wharf was never built, so tickets were sold directly on tramcars by the conductors. An “excellent” horse led each car, which moved no faster than 10 miles per hour (16 kph).Walk up Victoria Road and then turn right up King Edward Parade.

Beach Road

From the wharf, the tramway briefly ran down the centre of Victoria Road before turning onto Beach Road (now King Edward Parade). A primary appeal of the tramway was to bring tourists and prospective property buyers to the beaches of North Shore. To do so, the company built a stone retaining wall 5-8 feet high along Devonport and Duders Beaches to support the weight of the tramcars and ensure the integrity of the right-of-way. It also allowed for an unimpeded view of Waitematā Harbour, which must have been impressive to those unfamiliar with the area.Continue along King Edward Parade.

Church Street

The tramway had two regular stops along the line, the first being Church Street. This location marked the start of the North Road to Lake Pupuke and Waiwera Hot Springs. It also hosted Devonport Wharf. In the mid-1880s, the wharf and businesses along Church Street were still competitive with those on Victoria Road and it was likely a popular stop for commuters and residents.Continue along King Edward Parade.

Duders Beach

From Church Street, the tramway continued around Pilot (Torpedo) Bay. Duders Beach marked the halfway point of the line, where a siding may have been located for tramcars to pass. A one-way trip on the tram took about 20 minutes. However, departure times varied widely to match the ferry timetable and often only one car operated at a time. During the inaugural ride, the Star reported “general satisfaction being expressed with the easy travelling of the cars.”Continue along King Edward Parade.

Alison's Corner

The only difficult curve on the line was at Alison’s Corner, where tramcars turned up Cheltenham Road. During construction, the tramway company had to recall its engineers to install a wider curve, a task that resulted in a lawsuit when the company failed to pay for the extra work. This section was also the worst maintained since the track ran down the middle of the road and travellers rode their omnibuses, wagons, and horses over it without concern.Turn left up Cheltenham Road.

Jubilee Avenue

The second stop along the line was probably Jubilee Avenue, where property developers hoped to sell land. Visitors could also detrain here to visit Devonport Domain. In 1886, the Domain was a grassy field where cricket, rugby, and football games were played. The bowling green and tennis lawn were not added until the late 1880s. Jubilee also marked the highest elevation along the tramway at 12 metres above sea level, which journalists on the initial run reported as “being a short bit, which is at a very easy gradient.”Continue along Cheltenham Road.

Lake Street

Down Cheltenham Road another block, a spur was installed up Lake Street (Tainui Road) to William Street (Eton Avenue). It was here that the company built its stable and carbarn, “a commodious and convenient structure, excellently adapted for the comfort of the horses and convenience of the traffic.” The stable was a tall barn that dominated the surrounding buildings, while the carbarn was a canvas-wrapped, barrel-vaulted structure that sat in the field beside the stable.Continue along Cheltenham Road.

Cheltenham Beach

Still further down the road, the tramway reached its Cheltenham Beach terminus. Here and at Victoria Wharf, the tramcar’s horse would be detached from one end of the car and reattached to the other to reverse the journey. Where McHugh’s restaurant sits on the beach today, in 1886 the area was barren. Nonetheless, Cheltenham had been a primary attraction since the 1860s, when William Cobley laid out magnificent gardens on an adjacent 40-acre lot. He named them after Cheltenham Gardens in England, and developers jumped at the opportunity to sell nearby properties for baches and weekend homes.During a picnic at the beach after the inaugural ride, company chairman Graves Aickin promised that the party “had on that occasion seen but a portion of the line, which was to be extended considerably as funds would permit.” Indeed, plans from the beginning promoted branches to Lake Pupuke, Narrow Neck, and Stanley Bay. He guaranteed that the “portion already constructed would certainly pay, and when extended it would pay better.” And then he asked that “all interested in the district would come forward and take a few shares.”Aickin was not naïve. He understood that the tramway would not be an immediate success and argued that, “although the times were very dull, there was good reason to hope for the future success of their undertaking, for as the North Shore was one of the most beautiful localities around the city, there was sure to be an increase of population there, if anywhere.” He was correct, but about two decades ahead of his time.In the end, the Devonport and Lake Takapuna Tramway failed to convince investors or the public. By February 1887, lawsuits and debt forced the company to dissolve. The franchise was taken over by R. & R. Duder, local merchants, but they quickly gave up on the tramway. The tracks languished until December 1894, when they were taken up. Despite several efforts to resurrect the project, Devonport never again built a tramway.